IMAGINARIA POSTMORTEM

So it's being now a bit more than 5 years since I stepped onto Antarctic soil for the first time, and it's being about two weeks since Imaginaria, this little walking sim I made about that, came out too.

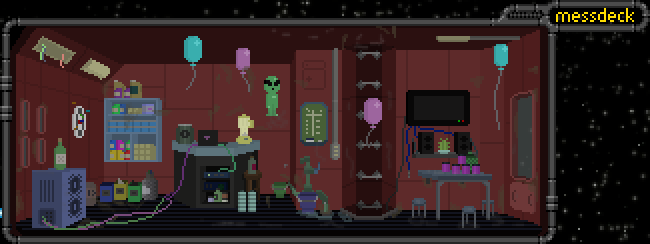

For this postmortem I'd like to tell the story from the start. I'd say Imaginaria had very little preproduction. In fact, one day I just woke up (in someone else's bed, since I've been homeless for while now, but that's a story for another time), grabbed my tablet and just started drawing the game's first location (the tomato interior). The image used in the game is exactly the same one I did that morning. A few days after, maybe even the next day, I had a little proof of concept to show what I was doing. It was like I needed to purge this game out of my body.

Of course, this game was in my head for a long time before that, probably from the moment I realised I was really going to Antarctica, so I think that's a good start for this story.

Where it all began

Many people ask me, when I mention I was down in Antarctica, how I got there. It's a good question, there are no cities down there, you can't really go just because, you need a mission. Antarctica in its whole is protected from economic and military activities (though they allow some tourism) under the Antarctic Treaty in force since 1961. This treaty sets aside Antarctica as a scientific preserve, establishes freedom of scientific investigation, and bans military activity on the continent. There are many research stations from the many countries that signed this agreement, some of them are permanent and some of them only receive people in the summer.

So, the way to get there, if you're not a researcher with specific subjects about Antarctica, is to be part of the support crew. Researchers go and do their research, but they still need a whole lot of infrastructure to do it: transportation, living accommodations, telecommunications, and even some entertainment. Me, as a systems engineer, was the perfect candidate for a support crew position, and people in summer had me running all over the place fixing their machines and computers.

The real answer on how I got there is a bit boring though: one day I googled "work in Antarctica", pressed the first link, applied, and after a long and tortuous selection process that included exams on basic computer operations, telecommunications and electronics and physical and psychological tests of all kinds, I was selected to go and stay down there for two summers and one winter as the chief for the Earth Sciences and Telecommunications Laboratory.

By this point in my life I was already making videogames, so there was never any doubts about making a game about this experience, the thing was what to make. The summers were really exhausting, on top of my regular work in the lab, I had to do the aforementioned support for everyone else in the station, and with an overcrowded station, I had very little space of my own both in my room and in my mind. Also, it was light outside almost the 24hs and that's just crazy. You can put all the cardboard you want in the windows and completely seal everything but you know the sun is still up there, mocking you.

Winter was the total opposite, almost no work at all, only the winter crew (we were a total of 26) remained, and most kept to themselves. It was during this time that I took two really good decisions: the first one was to learn pixel art, by doing tutorials and stuff. I had tried many times before to do this, I always liked drawing, even though I was really bad at it, but I was never consistent enough to be able to do anything remotely nice. Well, this time it kind of worked, and I could produce a few drawings I liked and everything. Second decision was to make RenJS, a JS/HTML5 visual novel engine that allows you to just write the game like a movie script, and adds a simple way of interaction. These two things are the base of Imaginaria, that I made with RenJS, and with my own pixel art.

I made a few other projects during winter too, of course. Most notable, a little JRPG with RPG Maker MV for my then gf's birthday (you can play it here, it's about magic and cats), and a little text adventure engine (that was also going to be called Imaginaria) that never saw the light. But apart from that I didn't really make any real Antarctic game.

The truth also is that Antarctica is overwhelming. Everything is gigantic, the ice, the animals, the Milky Way. Makes you feel very little. I found myself many times crying out of the sheer beauty of it all, double rainbow guy style (RIP my friend). Trying to put any of this into words was, and still is, very hard. Trying to make a game, way harder. So there I was, with so many things to tell and so little words.

A helping hand

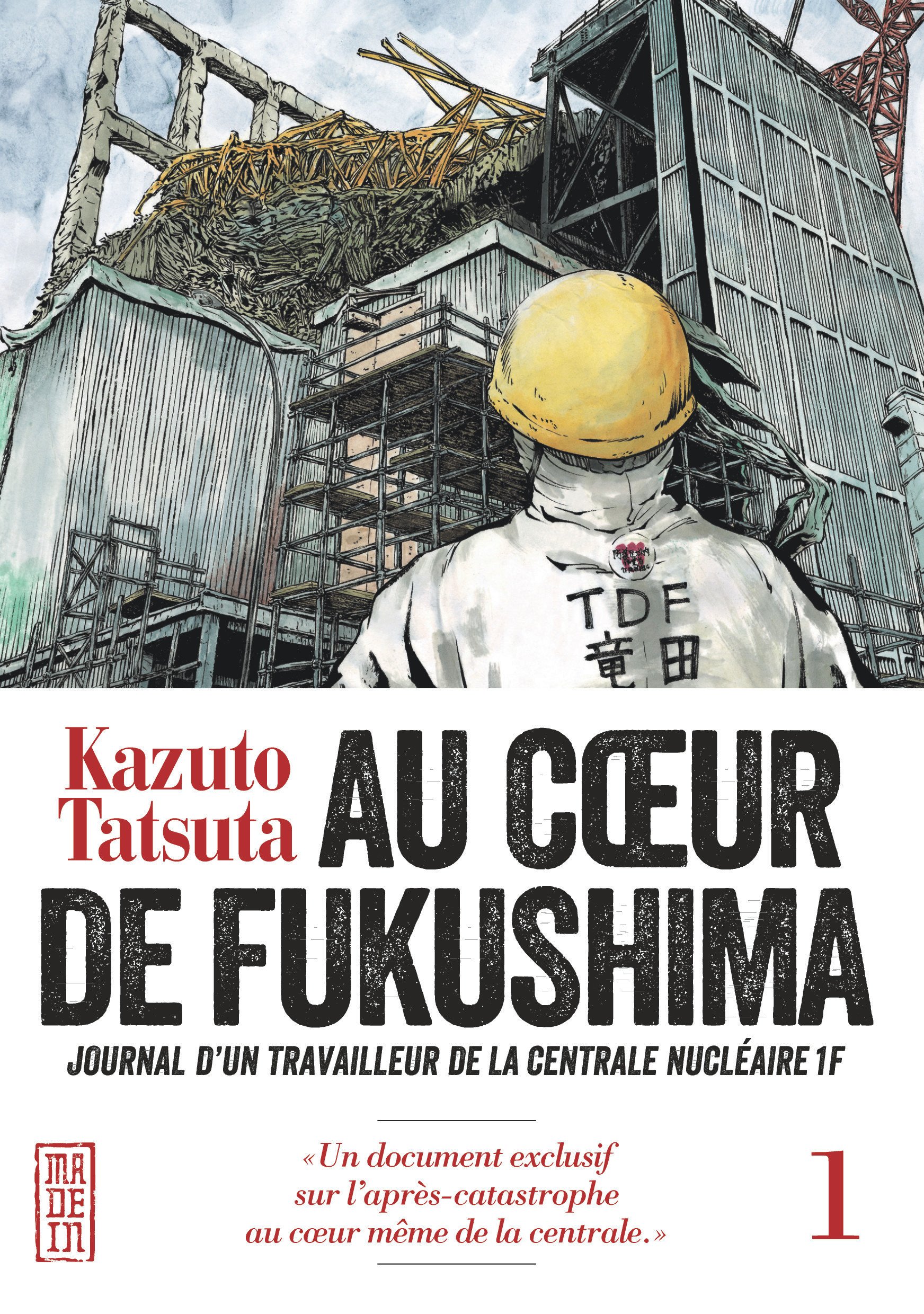

The last piece of the puzzle, came years later, in 2020, in the middle of the pandemic. After Antarctica I got a job as the team leader of a little group of software engineers in a research institute in France. That was a whole other experience, that ended up crashing and burning just after a few months of strict confinement, leaving me with lots of free time to just read and code and stare at the low ceiling of my attic flat (I'm still unemployed and more or less homeless, so please buy my games!). It was during this time that I started going to the biblioteque a lot, that had a great comic book section. The French love Japan, as much as Japan loves France, so there was a huge manga section that I read almost completely. Among these mangas I found one that inspired me to do Imaginaria as I did it, called Au Coeur de Fukushima (in the heart of Fukushima), by Kazuto Tatsuta. Sadly, no English edition yet, but if you can read French, you should totally get it.

We all know about the Fukushima accident after the earthquake in 2011. Much like the Chernobyl accident, the subject always fascinated me, so that's why I picked the manga in the first place, that promised a first person account of a relief worker on site. This work functions as an amazing kind of documentary, telling without any flourish and with lots of detail how it was to live and work in the restricted zone in the Nuclear Center, but without ignoring also the human side of such an endeavor. For example, it shows the recruiting process, the equipment and tools used, the living arrangements, etc. I loved it.

The manga comes in three volumes, written at different moments during his time working on and off the station. The first and third volumes center around two specific missions, the first one working in one of the "support" houses for the station workers, and the other one as an actual "cleaner". The second volume is in between these two missions, when Tatsuta had finished his first mission and didn't even know if he could ever go back, and centers around the creation of the manga itself.

This second volume was exactly what I needed to hear, what made me just start drawing and writing that November morning. In it, Tatsuta recounts his own doubts and fears about making such an oeuvre, which were almost the same as mine. First of all, would anyone care about it? Antarctica/Fukushima are really interesting places for what they represent and how they're exclusion zones where most people can't go freely. Life's different there as we know it, and there's many things to tell about it, yes. But they're just that, places. They're not stories in themselves, and for the mediums we chose for our respective creations, we both felt unsure about making something without a story in the usual sense. He thought at first to use the setting for a sci-fi story, with a touch of realism, and I did the same thing, but these efforts went nowhere. It didn't feel right to use the experiences as a backdrop for a fictional story, when the whole thing was that it was all real. But would a documentary thingy would be interesting enough on its own? Well, Tatsuta did it, and I loved it, so why not try it myself?

But there was another thing that affected both of us too, and that was the desire of going back. There's a reason why these places are so mysterious and not a lot of people know how's life down there. If you talk too much, too openly, too publicly about some of the things that happen (even if they're not strictly bad or illegal) you'll be marked, and probably won't be able to go back. So anonymity was something important for both of us, and the reason why Imaginaria won't be ever translated to my native language. I'm happy that Tatsuta was able to go back to Fukushima, and got one of the nice jobs. Me, I haven't gone back, and I see it every time farther away, but I still keep some hope.

Imaginaria

Finally, what else can I say about the game itself, that the game itself doesn't say. There are some artistic liberties about it. The station was way bigger, I merged some buildings: the cold storage chamber and the power station where in two dedicated houses, one next to the other, instead of together under one roof. The "main house" and the "meteorology lab" where also two different buildings. The main house had the kitchen, mess hall and laundry room, along with bedrooms for the chief, second chief and XO, and the meteo lab had, besides from the lab, the radio station, the weird cyber café room and many bedrooms, mostly unused throughout the year. I missed quite a few buildings too, like the diving and sailing section, a small office next to the sea with the AIS (a system to track ships all over the world), an aquarium building that was under construction the year I was there.

There was also a tiny catholic chapel where I never set foot, not even once. When I was doing the game I asked the biologist what was inside this building and he told me he hadn't entered neither. Se we'll never know. The priest of the station was the divers chief, he's a really cool guy, and was selected as the crew's priest one day he missed work, so he couldn't refuse. The mechanic workshop is another place that I couldn't remember inside very well. I did enter a few times, but not many. It's a good time to say that most of the crew was military, and only the biologist, my lab partner and I were civilians. Some of the military didn't like us much, but we were mostly ok with each other. The chief was a surprisingly cool guy once he found love during summer, among the researchers, and mellowed out.

Every one of the anecdotes I recount in Imaginaria are true, even the most macabre. I wanted to tell all of them somewhere, and here they are. Now that I took this weight off of me, I feel like I can go back to using Antarctica as an ambience for other things. Maybe I'll even finish that Antarctic inspired space opera visual novel I started doing so long ago.

And that's all, this ended up way longer than expected, so if anyone is still here reading, thank you very much, and say hi to the cats for me. Cheers!

lunafromthemoon, expeditionary of the white desert

Comments

Post a Comment